By: Dr. Mercola (2012)

Source: Mercola.com

A little over 100 years ago a German scientist wrote a letter to a company that made soap, and in so doing changed the way the world cooks its food. The soap company, Procter & Gamble, bought the scientist’s idea—and Crisco was born.

At this time in history, people used animal fats for cooking in the form of lard and butter. And while Crisco was purposely formulated to resemble lard and cook like lard, it was nothing like lard. The rest of the story, as related in The Atlantic, is a tale of marketing success.

When Marketing Alters Dietary Recommendations…

Recipe in hand, Procter & Gamble launched a massive sales strategy for Crisco that rivals even some of the biggest sales pitches today, and won over the cooks of the world. According to The Atlantic:

“Never before had Procter & Gamble — or any company for that matter — put so much marketing support or advertising dollars behind a product. They hired the J. Walter Thompson Agency, America’s first full service advertising agency staffed by real artists and professional writers.

Samples of Crisco were mailed to grocers, restaurants, nutritionists, and home economists. Eight alternative marketing strategies were tested in different cities and their impacts calculated and compared. Doughnuts were fried in Crisco and handed out in the streets. Women who purchased the new industrial fat got a free cookbook of Crisco recipes. It opened with the line, “The culinary world is revising its entire cookbook on account of the advent of Crisco, a new and altogether different cooking fat.” Recipes for asparagus soup, baked salmon with Colbert sauce, stuffed beets, curried cauliflower, and tomato sandwiches all called for three to four tablespoons of Crisco.”

Since advertising claims back then were unregulated, Procter and Gamble sold this plant-based product (known today as hydrogenated vegetable oil) as being healthier than animal fats, and consumers believed it. It took 90 years before researchers finally discovered that this new, “better-for-you” compound, which we call trans fat today, actually increases your risk of getting heart disease. As stated in the featured Atlantic article:

“It is estimated that for every two percent increase in consumption of trans fat (still found in many processed and fast foods) the risk of heart disease increases by 23 percent. As surprising as it might be to hear, the fact that animal fats pose this same risk is not supported by science.”

Not only that; research has also found that trans fats contribute to cancer, bone problems, hormonal imbalance and skin disease; infertility, difficulties in pregnancy and problems with lactation; low birth weight, growth problems, and learning disabilities in children. It’s so bad for your health that one U.S. government panel of scientists determined that man-made trans fats are unsafe at any level…

What History Can Teach Us

The article in The Atlantic, which is excerpted from the book The Happiness Diet by Drew Ramsey, MD and Tyler Graham, is a fascinating piece of history, and well worth reading in its entirety. It adeptly describes the cultural backdrop that led to this “fake lard” being accepted and embraced, not to mention the sheer power of aggressive marketing. Here’s just a short excerpt of this excellent piece. For more, please see the original article, or the book, The Happiness Diet:

“… Thanks to Procter & Gamble the United States boosted the production of a waste product of cotton farming, cottonseed oil… Before processing, cottonseed oil is cloudy red and bitter to the taste because of a natural phytochemical called gossypol… and is toxic to most animals, causing dangerous spikes in the body’s potassium levels, organ damage, and paralysis. An issue of Popular Science from the era sums up the evolution of cottonseed nicely: “What was garbage in 1860 was fertilizer in 1870, cattle feed in 1880, and table food and many things else in 1890.”

But it entered our food supply slowly. It wasn’t until a new food-processing invention of hydrogenation that cottonseed oil found its way into the kitchens of America’s restaurants and homes.

Edwin Kayser, a German chemist, wrote to Procter & Gamble on October 18, 1907, about a new chemical process that could create a solid fat from a liquid. The company’s researchers had been interested in producing a solid form of cottonseed oil for years, and Kayser described his new process as “of the greatest possible importance to soap manufacturers.” The company purchased US rights to the patents and created a lab on the Procter & Gamble campus, known as Ivorydale, to experiment with the new technology. Soon the company’s scientists produced a new creamy, pearly white substance out of cottonseed oil. It looked a lot like the most popular cooking fat of the day: lard. Before long, Procter & Gamble sold this new substance (known today as hydrogenated vegetable oil) to home cooks as a replacement for animal fats.”

The Saturated Fat Myth

The myth that saturated fat causes heart disease has undoubtedly harmed an incalculable number of lives over the past several decades. While it may have begun as an unsupported marketing strategy for Crisco, this mistaken belief began solidifying in the mid-1950’s when Dr. Ancel Keys published a paper comparing saturated fat intake and heart disease mortality. Keys based his theory on a study of six countries, in which higher saturated fat intake equated to higher rates of heart disease. However, he conveniently ignored data from 16 other countries that did not fit his theory.

Had he chosen a different set of countries, the data would have shown that increasing the percent of calories from fat reduces the number of deaths from coronary heart disease. And, if all 22 countries for which data was available at the time of his study are included, you find that those who consume the highest percentage of saturated fat have the lowest risk of heart disease.

Unfortunately, the idea that saturated fat is bad for your heart has become so ingrained in the medical and health community that it’s very difficult to break through that misinformation barrier. Still, the fact of the matter is that the saturated fat-heart disease link was a hypothesis that did not stand up to further scrutiny. Gary Taubes discussed this lack of evidence in an interview I did with him last year.

[Video removed from YouTube]Less Saturated Fat in Your Diet = Higher Risk of Heart Disease

Since the introduction of low-fat foods, heart disease rates have progressively climbed, even as studies kept debunking Keys research—repeatedly finding that saturated fats in fact support heart health. For example:

- A meta-analysis published two years ago, which pooled data from 21 studies and included nearly 348,000 adults, found no difference in the risks of heart disease and stroke between people with the lowest and highest intakes of saturated fat.

- In a 1992 editorial published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, Dr. William Castelli, a former director of the Framingham Heart study, stated:

“In Framingham, Mass., the more saturated fat one ate, the more cholesterol one ate, the more calories one ate, the lower the person’s serum cholesterol. The opposite of what… Keys et al would predict…We found that the people who ate the most cholesterol, ate the most saturated fat, ate the most calories, weighed the least and were the most physically active.”

- Another 2010 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that a reduction in saturated fat intake must be evaluated in the context of replacement by other macronutrients, such as carbohydrates. When you replace saturated fat with a higher carbohydrate intake, particularly refined carbohydrate, you exacerbate insulin resistance and obesity, increase triglycerides and small LDL particles, and reduce beneficial HDL cholesterol. The authors state that dietary efforts to improve your cardiovascular disease risk should primarily emphasize the limitation of refined carbohydrate intake, and weight reduction.

The Cholesterol Myth

Another example of tragically incorrect diet advice is the idea that dietary cholesterol is bad for your heart. Just as the saturated fat myth created an entire industry of harmful low-fat products, the cholesterol myth has given rise to a similar industry of highly processed fake foods posing as healthier alternatives. Take Egg Beaters for example. Introduced in 1972, Egg Beaters has been hailed as a healthy substitute for whole chicken eggs. It basically contains egg whites with added flavorings, vitamins and gum thickeners, providing you with no or low saturated fat and cholesterol, and fewer calories than regular eggs.

This is a tragedy, considering how nutritious whole eggs are—provided they’re from organically raised free-ranging hens. For example, egg yolks have one of the highest concentrations of biotin found in nature. So for 40 years, many Americans have deprived themselves of one of the most nutritious foods on the planet, while epidemiological studies repeatedly show that dietary cholesterol is not related to coronary heart disease incidence or mortality, so there’s no reason to fear eggs!

Your Body NEEDS Saturated Fat

But let’s get back to the issue of saturated fats versus trans fats found in Crisco and other vegetable oils. Foods containing saturated fats include:

- Meat

- Dairy products

- Tropical oils like coconut and palm oil

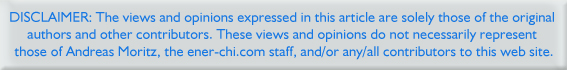

These (saturated) fats from animal and vegetable sources provide a concentrated source of energy in your diet, and they provide the building blocks for cell membranes and a variety of hormones and hormone-like substances. When eaten as part of your meal, they increase satiety by slowing down absorption. In addition, they act as carriers for important fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K. Dietary fats are also needed for the conversion of carotene to vitamin A, for mineral absorption, and for a host of other biological processes.

Saturated fats are the preferred fuel for your heart, and are also used as a source of fuel during energy expenditure. Furthermore, saturated fats:

Trans Fat and Sugar are the True Culprits of Heart Disease

Now, some research still suggests there is an association between fat and heart disease. The problem is that most such studies make the crucial error of not differentiating between saturated fat and trans fat. Additionally, the other primary ingredient in processed food that plays a role in heart disease is sugar, specifically fructose. Most researchers have failed to control for these variables. If researchers were to more carefully evaluate the risks of heart disease by measuring the levels of fructose, trans fat, and saturated fat, they would likely validate what I’ve been teaching for decades.

Both fructose and trans fat are known to increase your LDL levels, or “bad” cholesterol, while lowering your levels of HDL, known as “good” cholesterol, which, of course is the complete opposite of what you need in order to maintain good heart health.

It can also cause major clogging of arteries, type 2 diabetes and other serious health problems. It’s important to realize that it’s virtually impossible to achieve a nutritionally adequate diet that has no saturated fat. What you don’t need, however, are trans fats and fructose in excess of 15 grams per day. Since the average adolescent is now consuming in the neighborhood of 75 grams of fructose per day, one can begin to understand why we obesity and heart disease are at epidemic levels.

Healthy Fat Tips to Live By

Remember, you do need a certain amount of healthy fat, while at the same time you’ll want to avoid the unhealthy varieties. The easiest way to accomplish this is to simply eliminate processed foods, which are high in all things detrimental to your health: sugar, carbs, and dangerous types of fats. And don’t fall for labeling tricks designed to hide trans fat content.

In recent years many food manufacturers have removed trans fats from their products. However, the FDA allows food manufacturers to round to zero any ingredient that accounts for less than 0.5 grams per serving. So while a product may claim that it does not contain trans fats, it may actually contain up to 0.5 grams per serving. If you eat a few servings, you’re quickly ingesting a harmful amount of this deadly fat. So to truly avoid trans fats, you need to read the label and look for more than just 0 grams of trans fat. Check the ingredients and look for partially hydrogenated oil. If the product lists this ingredient, it contains trans fat.

After that, these tips can help ensure you’re eating the right fats for your health:

- Use organic butter (preferably made from raw milk) instead of margarines and vegetable oil spreads. Butter is a healthy whole food that has received an unwarranted bad rap.

- Use coconut oil for cooking. It is far superior to any other cooking oil and is loaded with health benefits. (Remember that olive oil should be used COLD, drizzled over salad or fish, for example, not to cook with.)

- Following my nutrition plan will automatically reduce your modified fat intake, as it will teach you to focus on healthy whole foods instead of processed junk food.

- To round out your healthy fat intake, be sure to eat raw fats, such as those from avocados, raw dairy products, and olive oil, and also take a high-quality source of animal-based omega-3 fat, such as krill oil.

As for how much fat you might need, government guidelines are sorely in need of reconsideration. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommends between 20-35 percent for adults, and 25-35 percent for children between the ages of four and 18. The US Department of Agriculture’s dietary guidelinesv are even more ill-advised, recommending you to consume less than 10 percent of calories from saturated fats.

As I and other nutritional experts have warned, most people actually need upwards of 50-70 percent healthful fats in their diet for optimal health! My personal diet is about 60-70 percent healthy fat, and both Paul Jaminet, PhD., author of Perfect Health Diet, and Dr. Ron Rosedale, M.D., an expert on treating diabetes through diet, agree that the ideal diet includes somewhere between 50-70 percent fat.

To view the original article click here.

To reprint this article, visit the source website for reprinting guidelines.