By: Wolverine

Source: roarofwolverine.com

The overuse of the procedure known as colonoscopies as a prophylactic for colon cancer, has not only become quite a fad in recent decades, but also a multimillion dollar industry. Every year, over 14 million perfectly healthy individuals age 50 and up, submit themselves to this invasive procedure in the hope of receiving protection from colorectal cancer. Do the benefits of this screening outweigh the risks involved?

Sometimes in this world, a treatment may be as dangerous as the disease itself. I serve as a living testament to the severity of the damages possible with this procedure. The many injuries that can be caused by colonoscopies, the anesthetics and preparation required for this procedure, is what I would like to cover in part 1 of this series.

I would like to preface this by saying that colorectal cancer is a very real, frightening and deadly disease, and I am in no way lightening that fact. But, a colonoscopy injury can be as lethal and cause as much fear and suffering as colorectal cancer itself. So, which one carries the greatest risk of actually happening to you in your lifetime? Especially between the age of fifty to sixty?

Reported in this study from 2006; “The perforation rate reported from colonoscopies was 1 in 1000 procedures, and ‘serious complications’ occurred in 5 in1000”. According The Annals Of Internal Medicine’s report on colonoscopies, an estimated 70,000 (0.5%) will be injured or killed by a complication related to this procedure. This figure is 22% higher than the annual deaths from colorectal cancer itself – the very disease the device was designed to prevent.

The average age for developing colorectal cancer is 71. The medical industry recommends screening starting at the age of 50 and as low as 45 for African Americans. So, for the first couple of decades, you are risking your life with a dangerous, invasive procedure to diagnose a disease that is far less of a risk at that age than the odds of being injured by the screening device. I could stop right there, because that should be enough to make a critical thinker forget about this barberic diagnostic tool, at least until the age of 65. But, there is more – a whole lot more to consider, which leads me to believe we should search to discover a safer and more effective tool.

Many of the related injuries associated with colonoscopies go unreported or are never diagnosed. Death from colon cancer will very rarely not be reported as the cause of death, so those are accurate predictions. But, we have no idea just how high the actual number for colonoscopy injuries and death may actually be

Typically, a patient left untreated for as long as I was will die. Had I died, the death report would say complications from necrosis of the bowels and mention nothing of the colonoscopy. Perforations and other injuries from colonoscopies can be extremely difficult to diagnose and are often of little concern when the patient is dying. We also have to consider that doctors and hospitals will rarely report an injury from a colonoscopy unless forced to. It is up to the patient to successfully prove that the procedure caused their injury or resulting infection in a civil trial before it will be reported and logged. The fact that few, if any, of these cases will see the light of day will be covered in my post “Is There Any Such Thing As Malpractice?”.

Even though statistics say that 70,000 people will be injured or killed by this procedure this year, the actual number is far greater. But even if you go by only those that have been forced to be reported, the number of injuries are still significantly higher than the incidence of colorectal cancer.

One of the more dangerous outcomes of a colonoscopy is the one I was a victim of – a perforation. Everyone considering this diagnostic procedure is required to sign a paper stating that they understand all of the injuries possible with this invasion of their organs with a mechanical device and the air pressure exerted in order to inflate the colon. The list of the horrific complications, including death, should be enough to give anyone pause. But, patients are immediately calmed when their doctors explains that these things are rare. The favorite tool of compliancy in the doctor’s arsenal is the phrase “I’m not worried about it”. They’re not the ones about to have a metal tube shoved four feet up their pooper and they also understand that by signing that paper, you have waived all rights to legal compensation if injured. Any wonder why they’re not worried? As long as your insurance checks out, they won’t break a sweat.

Other than perforations, there are other dangers, including a list of possible reactions to the general anesthesia that must be used during a colonoscopy. Though rare, they can range from deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolisms to pneumonia. No other cancer screening test requires a general anesthetic to be used. There can also be complications associated with the colon prep required for the procedure. This prep can include a 2 liter enema of synthetic laxatives administered about an hour before the procedure. This cocktail of chemicals can cause everything from deadly electrolyte imbalances (which can lead to congestive heart failure), to possible thrombosis in the mesenteric artery, to kidney damage.

If this diagnostic procedure still sounds safe to you, we will also throw in the newest discovery that has come to light in recent years. It is impossible to sterilize an endoscope! This high tech device cannot be boiled or steamed because high temperatures can destroy the sensitive electronics. There are many tiny nooks and crannies in and around the tip of the scope, which are impossible to clean, even by hand. Recent biopsies of these scopes have revealed encrustation of fecal matter, tissue, blood, and mucus imbedded from previous patients. At present, medical personnel bathe the scopes in a disinfectant solution. They’re not scrubbed. Not disassembled. Not heated. They’re rinsed in an ineffective bath of Glutaraldehyde, which if not rinsed off thoroughly, has been cited as a cause of toxic Colitis.

It is very possible, and clinically proven, that you can be infected by HPV (Human Papilloma Virus); HIV; Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Helicobacter pylori,; Hepatitis B and C; Salmonella; Pseudomonas and Aeruginosa; Flu Viruses and other common bacteria such as, E. Coli O157:H7 and Creutzfeldt- Jakob Disease. And the pathogens you may be infected with are typically going to be a hospital borne variety, which means they are strains that have been exposed to, and become immune to most antibiotics. Leading microbiologists have advocated using sterile, disposable parts for endoscopes as well as the use of a condom-like sheathes for each new patient. But, the manufacturers and health-care providers have resisted these solutions because of added costs. Isn’t that nice? These safety precautions are mandated in England, but not used here in the U.S.. The FDA even recognizes this problemhere, but acts as if their present recommendations are effective – they have been proven not to be.

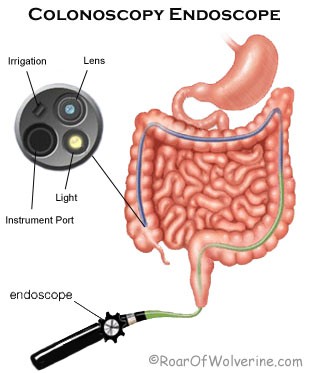

Following my transplant, I was required to undergo an ileoscopy, including biopsies, weekly to check for signs of rejection. Patients are not anesthetized for this procedure because the scope is inserted into a stoma, rather than the anus, so it is painless. I was allowed to watch the procedure on a television monitor. They would fish a tool (similar to an alligator clip) through the instrument port of the scope (refer to image at the top of page), to tear off a piece of villi for a biopsy. Each time I could see a tiny injury which would begin to bleed. An open, bleeding wound near the tip of a scope encrusted with fecal matter – sounds like a real good medical practice. Each time you undergo a colonoscopy they may clip out a piece of your intestine for biopsy or snip off a polyp. There will be an open wound and mixing of your blood with whatever may be lingering on the end of that scope which has been in hundreds of other colons and is unable to be sterilized.

A few days after one of the scopes, I came down with a systemic gram negative rod infection called pseudomonas, a very deadly pathogen to immunosuppressed patients. The particular strain that I had was identified as being multi-drug resistant, meaning it was certainly a hospital borne variety. It nearly ended my life as I succumbed to septic shock and by the time the ambulance arrived at the ER, my blood pressure had dropped to 35/28 and I was given a very small chance of surviving the night. Before intubating me, they told me they would send in my wife so I could say “goodbye” to her for the last time – this is how sure they were I would never awake from the anesthesia.

It is quite obvious now that I contracted that pathogen from the scope I had just received two days before (I failed so quickly because I was so immunosupressed from the transplant). Seven months prior to that, I had been the victim of a perforation as the result of a routine colonoscopy, which ultimately cost me all of my intestines and nearly my life. That is two near death injuries on just one patient within seven months from endoscopes.

I met six other transplant patients in the last two years. Three out of those six people, adding myself (making seven), had suffered a perforation from scopes and a fourth one had suffered a perforation in a similar invasive procedure. Two of those patients died as a result of their injuries and I nearly died both times from mine. The third transplant recipient needed an emergency resection of her newly transplanted bowels because of a perforation from a scope. The baby of our transplant family, a young woman only 28 years old, is fighting a Klebsiellasepsis at this time, which was most likely transmitted via a recent scope. “Injuries and perforations from colonoscopies are rare” my ass!

Because of what happened to me and the manner in which the doctor lied to me about the rarity of these injuries is what has motivated me to study and investigate the subject for the last two years. I have discovered that perforations are not as rare as the doctors would like us to believe. But at a charge of $1,500.00 to $2,000.00 per procedure and the fact that some gastroenterologists can rush in as many as 30 -40 procedures a day, it is not hard to see a motivation to suppress the truth about the dangers and your risk of being perforated or infected by this medical fad.

From an a 2006 article in The New York Times; “… if our group is representative of an average group, you will see people (doctors) who take 2 or 3 minutes and people (doctors) who take 20 minutes to examine a colon. Insurers pay doctors the same no matter how much time they spend.” It is often about quantity, not quality and your risk of being injured increases the faster the practitioner attempts to finish your procedure, not to mention the efficiency of the cancer screening falls dramatically when hurried.

I hope that one day this killer will end up on the junk pile of quack medical devices from the Victorian Age, and I hope I can have a hand in placing it there. This will not be easy. The medical industry now has celebrities, such as Katie Couric, actively using their fame to promote this procedure as a life-saving miracle, rather than the barbaric medieval medical device it really is. They used the fact that Katie lost her husband to colon cancer and swooped in on this grieving widow and convinced her this “snake oil” medical device could have prevented it. I am sure that the fact that NBC is also owned by General Electric, a manufacturer of endoscopes, had little to do with sponsoring her televised colonoscopy and using her celebrity pitching skills to bring this killer to the forefront of common medical practices.

You may be thinking that I must have lost my mind, because after all, this procedure has effectively saved thousands of lives, or at least that’s what you’ve been led to believe by the medical industry and their advocates in the media. But is there any more truth to this than the lie that injuries are rare?

To view the original article click here.

To reprint this article, visit the source website for reprinting guidelines